An Observational Report and a Fable

Once upon a time, three instructors were talking about their students’ Similarity Reports from TurnItIn.com. The instructors lamented the department’s requirement to have students submit their work to be checked by a moderately accurate algorithm against a behemoth, exploitative database, but their efforts to resist, though emboldened by Morris and Stommel, were unsuccessful. Making the best of it, they decided to see what they could learn by comparing the distributions of similarity scores for each paper in their courses.

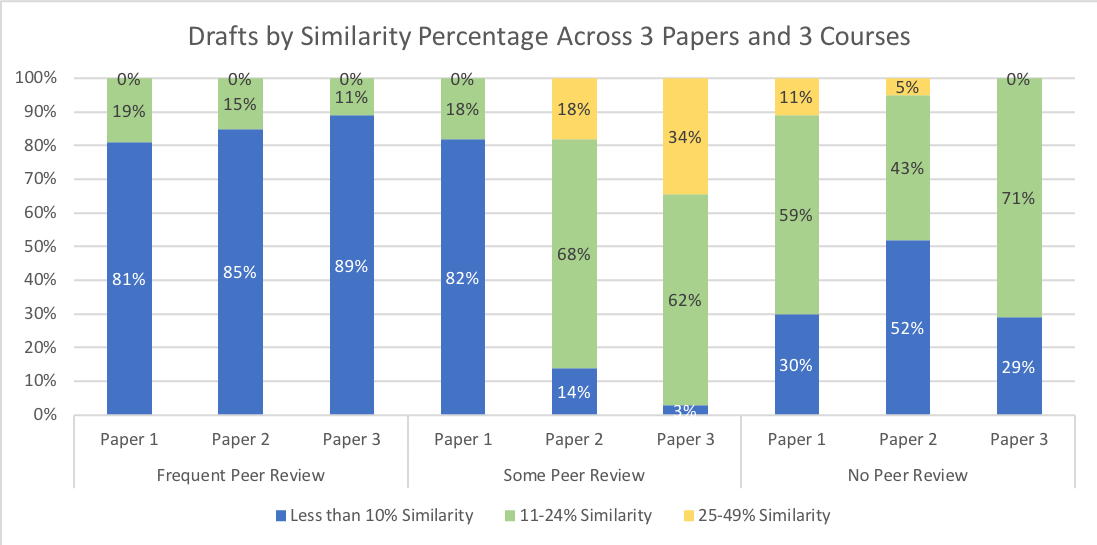

They noted that TurnItIn’s Similarity Reports categorize drafts based on the percentage of matching text:

- Blue Less than 10% similarity

- Green Less than 24% similarity

- Yellow 25-49% similarity

- Orange 50-74% similarity

- Red 75-100% similarity

They reminded themselves that some matching is desirable because one of the outcomes of the course is appropriate source use. Quotations, for example, might be reported as matching text, but a well-integrated quote is a strength of student writing rather than a weakness. They also agreed that too much similarity might indicate what Rebecca Moore Howard calls patchwriting or perhaps a more nefarious text-borrowing strategy. So, they agreed that they wanted to see some but not too much similarity between students’ drafts and other texts in the database.

All of the instructors were relieved to know that their students’ similarity scores fell in the lowest three categories. No instructor had a student with half or more of their draft matching other texts. But, it was clear that each class had a very different distribution of similarity scores for each paper.

The instructors noted with surprise that more than 80% students participating in frequent peer review had the lowest similarity scores in each of the 3 papers. In the courses using some and no peer review, the percentage of students with fewer than 10% matching text varied greatly across the assignments. More peer response correlated with more original writing.

Reflecting on these results, the wise instructors acknowledged that the frequency of peer review was only one factor influencing these patterns of similarity. The criteria for the papers were different across the classes, and each instructor emphasized the skills to a different degree. Plus, papers with requirements for using popular sources are more likely to be matched with Turnitin.com’s database than academic sources. But, they all agreed that it was both interesting and rather surprising that the students who shared their writing most and got the most feedback produced the most original writing.

Works Cited

Howard, Rebecca Moore. “A Plagiarism Pentimento.” Journal of Teaching Writing, vol. 11, no. 2, 1992, pp. 233-45.

Morris, Sean Michael and Jesse Stommel. “A Guide for Resisting EdTech: The Case Against Turnitin.” Hybrid Pedagogy, Jun 15, 2017.