Barbara D’Angelo, Clinical Associate Professor of Technical Communication at Arizona State University, has taught Research in Technical and Applied Communication (TWC505) in ASU’s fully online master’s program for 3 years. The purpose of the course is two-fold: to introduce students to research methods and to prepare students to research and write a proposal for their applied project or thesis, which they complete in the following semester. In 7.5 weeks, students learn about various research methodologies, identify and focus a research question, and draft a proposal for submission to their committee chair.

The hardest part is getting to an effective research question or statement. Students enter the course with a broad idea of what their applied project or thesis topic will be. For example, an applied project might consist of a usability study for the student’s employer. Or, a thesis project might entail some characteristic of social media use for workplace communication. Prior to using Eli, students would have trouble narrowing their question until the very end of the course, if at all.

Focusing a research question or statement takes time – something that is a luxury in a 7.5 week course. It usually involves making some decisions about what phenomenon they have the opportunity to study, followed by what indicators are relevant to understanding it, and what data comes from those indicators. Those are not easy decisions to make, nor is the need to make them terribly obvious to students planning their first big study. Feedback and revision, across a few cycles of thinking, help them see the need to make choices that narrow their study and gradually make some decisions. The stress of that deliberative process is intense for everyone.

Using Eli in Spring 2018, D’Angelo’s students developed better research questions faster. Three elements contributed to their success: scaffolded writing and review, elaborated feedback, and timely instructor feedback. Though these ingredients have always been part of her courses, D’Angelo found that Eli

helped in two ways. One, Eli provided a more structured and systematic environment for reviews than is possible in Blackboard. Two, that structure enabled students to engage in the discourse of peer review and revision so that their feedback was more constructive and targeted towards improvement.

Scaffolded Writing and Review

D’Angelo used a series of feedback and revision cycles to guide students through the drafting process:

- 3 sentence elevator pitch with peer review on specificity and significance of the research question or statement

- A short purpose statement draft with peer review on how clearly the gap/problem was explained

- 3 microstudies with peer review to practice connecting research questions with specific methods showing indicators of success such as data gathering processes, data type(s), and data analysis process

- full draft of the applied project or thesis proposal with peer review on methodology, specificity, and significance

The writing tasks increased in formality and complexity. In the elevator pitch, writers were encouraged to name the what, how, and why of their research in a quick conversation with a harried colleague. In the purpose statement draft, writers articulated the goal, research questions, and context for their work. In the microstudies, writers covered research questions, methodology, results, and significance, just like the expectations for the final proposal draft. They practiced the most important aspects of the final paper several times. From the elevator pitch to the final draft, writers used the feedback they received to revise their study plan.

Part of the revision support was also peer feedback, which in Eli Review is structured using instructor-designed checklists, ratings, and comments. D’Angelo designed reviews that targeted a few criteria at a time so that, like the writing tasks, review tasks built in complexity over time. For example, the purpose statement peer review is shown below in Figure 1. This review task repeats criteria from the elevator pitch (indicated by asterisk *) and introduces criteria that will be repeated in the micostudies and final thesis draft. Each week, reviewers practiced the same criteria they used in a previous week plus one or two more. This scaffold held most of the expectations constant with just a few new challenges while students experimented with different ways of articulating their projects.

Figure 1. Week 3 THESIS/AP: Purpose statement peer review questions

The draft

- clearly and concisely states the purpose/goal of the research*

- includes a specific and focused research question*

- explains the context of the research for the field of technical/professional communication

- is well-organized

- cites sources in APA style

- is well-supported with evidence

Rating Scales

☆☆☆☆

On a scale of 1 (low) to 4 (high), how well does the draft articulate a manageable research project that can be completed within one semester?

☆☆☆☆

On a scale of 1 (low) to 4 (high), how well does the draft articulate a problem, gap in knowledge, or other context within the field of technical/professional communication or the workplace?*

Contextual Comments

Saying “this is good” or “I like what you wrote” might help preserve relationships and make writers feel good. These encouraging comments may help the writer’s confidence, but they don’t offer ideas for improving the draft unless you to point to area where the writer can build on a strength. As a reviewer, your primary task is to provide constructive feedback for improvement.

Use the describe – evaluate – suggest model. To help, you might refer back to trait characteristics or the rating scale to provide specific suggestions.

As you compose your reviews, remember that you are referring to the draft, not the writer. Avoid using “you” as you write your comments.

* These criteria are repeated from the previous Elevator Pitch peer review.

Elaborated Feedback

D’Angelo focused reviewers’ attention on the most important criteria for each review using the checklists and ratings, then she required reviewers to put their feedback on the criteria into words in the final comment section. Her instructions for commenting prompted students to write elaborated feedback following Bill Hart-Davidson’s describe-evaluate-suggest model.The expectation that students follow the pattern in their comments intensified their practice. To give effective feedback, reviewers had to understand the research question well enough to make suggestions about how it could be revised. Instead of truncating feedback to label problems or merely mention criteria, reviewers were prompted to fully explain what they noticed, why it was a problem, and how to address it.

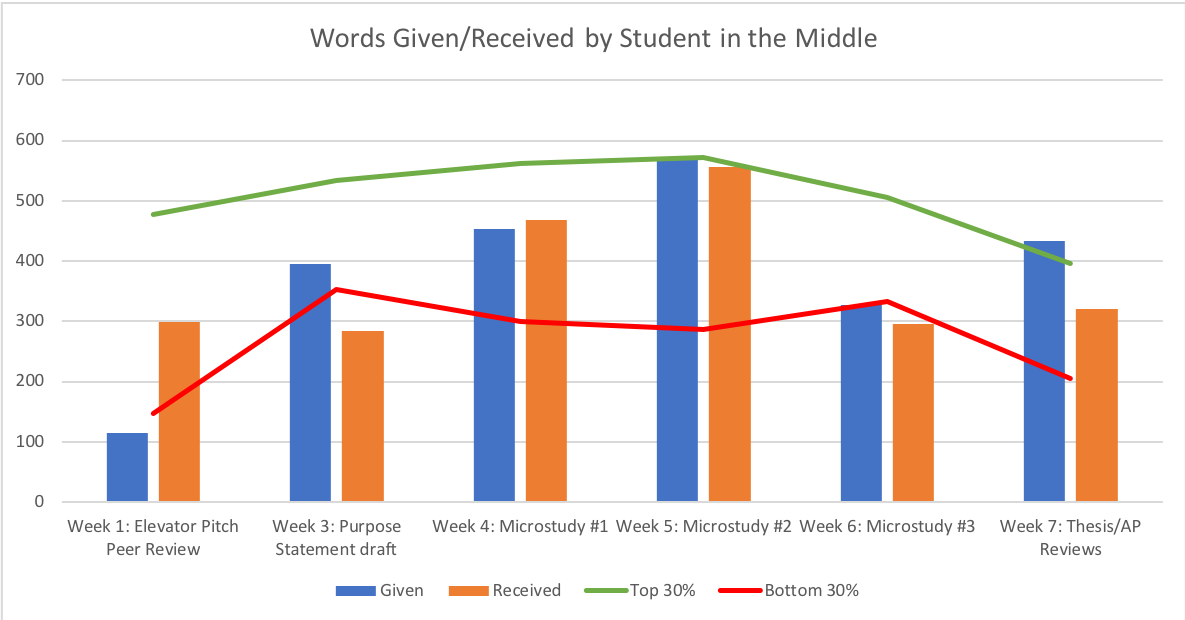

Rehearsing problem-criteria-suggestion reinforced students’ skills and constituted a significant portion of the workload of the course. Figure 2 below gives a sense of the writing practice students did through feedback exchange. It shows one individual student’s engagement. This student’s overall contributions fell in the middle of the group; they contributed around 2,300 words overall, which compared to the top reviewer at 2,900 words and the lowest reviewer at 1,700 words. Figure 2 shows how many words the student gave in feedback (blue bar) and received in feedback (orange bar) in these tasks; the student’s contributions are also compared to the top 30% of reviewers based on word count (green line) and bottom 30% (red line).

Figure 2 demonstrates that from Weeks 3-7, most students were writing 1-2 pages of feedback on the criteria as reviewers and were getting 1-2 pages of feedback from reviewers on their own writing. This immersion in talking about the criteria no doubt helped students make faster progress in refining their own research questions. Giving elaborated feedback required students to practice improving research questions, and that practice helped them make faster progress in their own writing.

More specifically, the level of feedback increased during week 3 for the purpose statement draft. In this assignments, students used their revision plans from week 1 (elevator pitch) to improve their research question or statement plus add background context for it. The increased amount of feedback in week 3 could be due to several factors. The student’s increased comfort level with Eli after using it for the previous assignment or the student’s greater understanding of expectations and criteria for conducting the reviews. However, D’Angelo observed that, compared to previous sections of the course, students started narrowing research questions/statements more effectively early in the course and leading into the microstudies. While questions/statements continued to be refined until the final draft proposal at the end of the course, the increased and more targeted discourse surrounding peer reviews appeared to D’Angelo to have assisted students to think through and reflect on their research and its context.

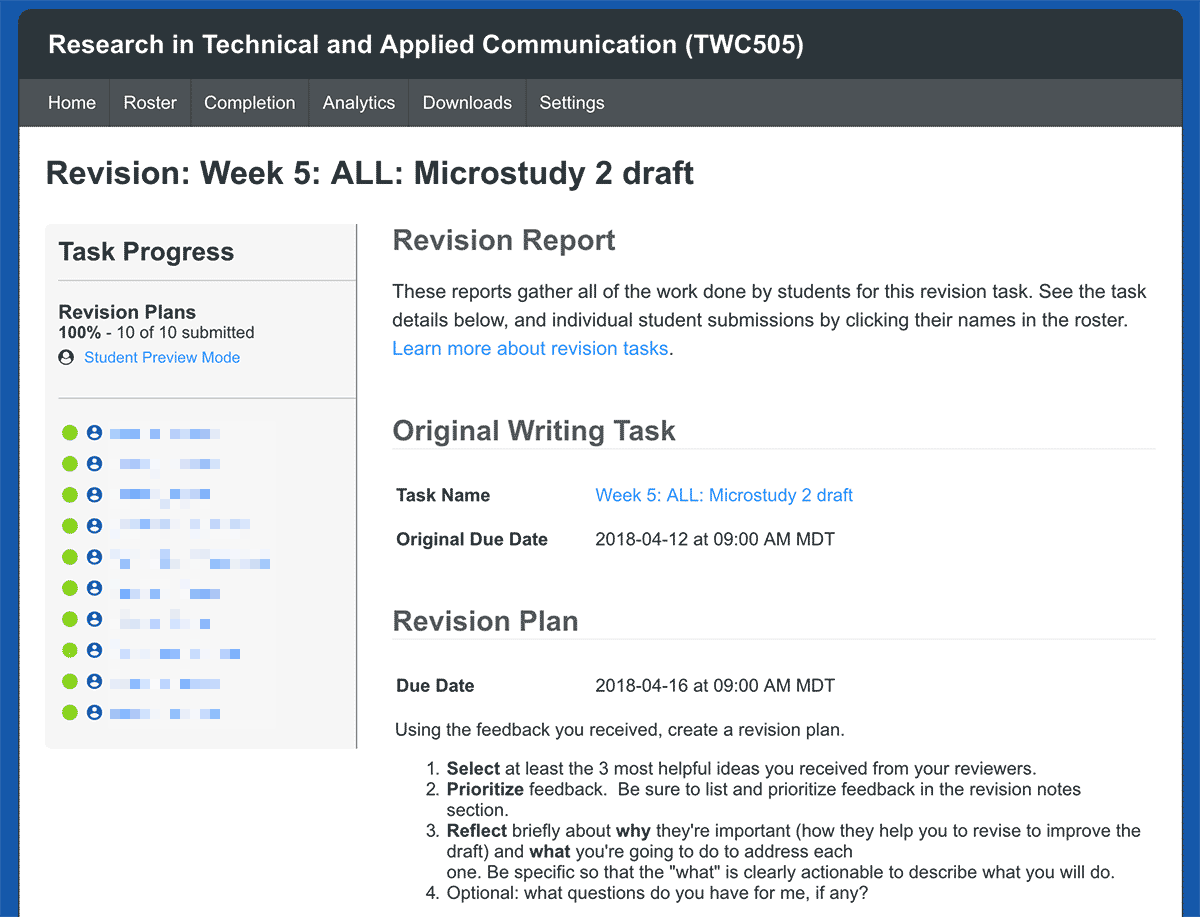

Timely Instructor Feedback

In a 7.5 week course, D’Angelo gave feedback to individual students six times. She used Eli’s revision plan to ask students to explain their revision priorities and goals based on peer feedback and their own insights. Then, she offered feedback on their decisions as writers and contributions and reviewers. She coached the decisions students were making between drafts rather than primarily marking-up drafts. She also encouraged students to use their revision plan to ask her questions about the assignment and/or their drafts and revision strategy. While not all students took advantage of this opportunity, for those that did, it provided a space to clear up confusion or ask questions about feedback they’d received that they disagreed with or was uncertain about.

For D’Angelo, giving feedback on revision plans was “intense but pedagogically valuable.” On the whole, responding to plans was about the same amount of work as her previous method of delivering instructor feedback. What changed was how she delivered it. By commenting on revision plans, she became part of the conversation of the review process. Since students had selected and prioritized feedback in their revision plans, D’Angelo was able to follow-up on them to affirm them or expand on them. In addition, she was able to engage with the student’s reflection with comments or questions to further help the student improve their work. In short, using Eli transformed her online course into a conversation between peers in which she was able to take part so that it modeled the workshop method.

More, Better, and Faster

In a short course, more, better, and faster seem too good to be true. In a 7.5 week course, using Eli means that students are engaged with a task deadline 4-5 days per week. In addition, using Eli meant increasing the rigor of drafts, reviews, and revisions. In this course, more practice with criteria helped students develop better research questions earlier than in previous semesters. That success came from how D’Angelo used Eli to

- provide clear instructions for small bits of writing and targeted reviews

- expect students to put the criteria into their own words through “describe-evaluate-suggest” comments

- intervene on the decisions students were making week-to-week.

Finally, Eli upped the ante for student engagement. It provided a space for students to engage with one another in the discourse of peer review and revision. And it gave them the language to do so effectively. That engagement and emerging knowledge of how to give and receive constructive feedback is an important skill and ability for technical communicators who are in and entering a field that requires team and project management skills and abilities. While the purpose of using Eli in the course was to help students to develop research proposals for their upcoming applied project or thesis, D’Angelo believes that it also potentially helped them to develop strategies, techniques, and the language needed to engage in constructive team and project management in their workplaces.