This post is a part of the series Challenges and Opportunities in Peer Learning.

Giving helpful feedback to other writers is challenging. There’s a lot to get right: notice strengths and weaknesses, explain why, and offer suggestions for improvement. Peer review is learning by doing, and that means mistakes are a valuable part of the process.

In Part 1 of this post, we acknowledged that some students think mistakes confirm their limited abilities. Carol Dweck’s research on a mindset shows that students with a fixed mindset (“I was a born a bad writer”) think of mistakes as confirming what they can’t do. These beliefs impact their confidence and commitment to peer learning.

In this post, we offer strategies for helping students view the mistakes they and everyone else makes in peer learning as a path toward improvement. We explain how to discuss mistakes from Dweck’s growth mindset.

Part 2: Strategies for Showing Students Their Growth

In this post, we want to confront students’ self-doubt in peer learning head on. They may have had less than positive experiences with peer response in the past. Helping them to see that it can go well and be a valuable use of their time is often an important first step. They’ll see the value as they gain confidence in their ability to give helpful feedback. They’ll gain even more when they see the payoff for working hard at giving feedback in their improvement as writers.

These five strategies can help instructors put the emphasis on reviewers’ growth.

Strategy: Check your own assumptions and get support.

Instructors’ view of error shapes peer learning too. In “Your Students Aren’t Revising Enough,” we acknowledged that many instructors view peer learning as risky because students give each other unhelpful feedback. Especially when they start, students will not know how to read and respond to a draft so that writers get what they need to revise.

After the first few reviews, instructors grapple with their own assumptions:

- Are students’ mistakes confirmation of “the blind leading the blind”? After all, Kenneth Bruffee’s defense of peer tutoring was in the context of a writing center, outside the boundaries of a typical class and with trained tutors.

- Or, are students’ mistakes in giving helpful feedback providing a map of what to teach next so that students can bring the criteria into focus as they talk with each other about their work?

Instructors operating from the first assumption find all the evidence they need to back away from peer learning. Bedore and O’Sullivan conducted surveys and focus groups with graduate instructors about their ambivalence toward peer review and self-assessment. Their findings suggest that experience alone talks new teachers out of these pedagogies. By contrast, Bedore and O’Sullivan found that new instructors who talked about their ambivalence with others worked through their own misgivings about the value of peer learning.

When (not if) you find yourself doubting peer learning as the best strategy you have from the front of the room to help all students improve, talk to a colleague. At Eli Review, we offer a range of professional development resources (including this blog series), and we’re happy to consult with you about what’s happening in your class. More than once, Bill Hart-Davidson has talked me (Melissa) off the ledge of quitting peer learning. Collegial support and professional development help keep skepticism in check. It takes a village for instructors to stay the course in peer learning long enough for students to improve at giving helpful feedback.

Instructors who have that village of support can operate from the second assumption. In fact, we have all the evidence we need to understand where our students need to improve too! And we have it before the first writing project is done, in time to act on it. From students’ mistakes, we figure out what to teach next. Explicit instruction on how to give helpful feedback becomes a routine (and powerful) part of class time.

Before talking with students about mistakes in peer learning, instructors should check to be sure they have a growth mindset too.

Strategy: Reframe the goal of giving feedback.

If you prepare students for their first round of peer review by asking them to read about how to give helpful feedback (perhaps using Eli’s “Feedback and Improvement”), then you might be surprised at how few students put those strategies into practice in the first round. Sure, they read the article. When they started giving feedback, however, they resorted to doing what they’ve always done: offering praise or suggestions. Reviewers are working from the stance that their job is to fix the draft or approve it.

But, feedback is more than fixes.The next step in teaching students how to give helpful feedback isn’t to discuss whether their praise or suggestion was correct. It’s not yet about right or wrong feedback.

The next step is to shift students’ sense of what the role of a reviewer is. Hattie and Timperly’s (2007) list of the three questions feedback answers is useful for this class discussion:

- Where am I going? (goals)

- How am I going? (description of current status)

- Where to next? (suggestions for how to do it differently or do more of it) (87-90)

Our materials re-order these questions and offer the pattern “describe-evaluate-suggest”; we have readings, videos, and sample comments that can be used for this direct instruction in being a helpful reviewer.

This phase of teaching peer learning focuses on examples. Reviewers need to see how the parts of an effective comment work together. They need to know how to phrase feedback so that it’s thorough and respectful.

For students who may have received only short marginal comments from English teachers in the past, writing 2-3 sentence comments is a new genre. Comment templates provide an effective scaffold at this stage. Here are several comment patterns that follow describe (D)-evaluate (E)-suggest (S):

- (D) Your draft opens with ____. It catches my attention because ___. (E) Since you are trying to reach ____ audience, this opening strategy might ________. (S) What if you continued that approach by ___? Going in this direction will help you _______.

- (D) I got lost in paragraph ____. So far, you’ve talked about _____. (E) I don’t see the connection between ____ and ____. (S) Try to add/reorder ____. Perhaps adding transition words like ___ or ____ will also make your logic clear.

- (D) You’re writing about ____, and your goal is ____. (E) Since, like your intended audience, I’m unfamiliar with your topic, I am confused. (S) Consider adding in more background details about ____ or ____. An example or story related to _____ might help too. Putting that info above/below paragraph _____ will help readers _____.

After a round of practice with teacher-provided templates, groups can also develop their own comment templates about specific criteria. Working together to think about how to phrase their insights can help them with the cognitive load of giving helpful feedback later. Comment templates are shortcuts that can keep the smoke from coming out of reviewers’ ears in these early peer learning experiences. They work like temporary ramps to help students level-up their review abilities.

Strategy: Set reasonable goals for growth by the third review.

As mentioned above, reviewers tend to give feedback from instinct during the first round of peer learning, defaulting to praise and suggestions. If instructors prioritize “describe-evaluate-suggest” in the second review, then that round will show some improvement.

By the third review, most reviewers should be consistent with those three moves. That means instructors should be able to detect changes in comments.

Reviewers should be offering fewer comments that

- Praise (“Good job!”)

- Are short (“Your thesis needs work.”)

- Point to sentence-level corrections (“Check your commas.”)

By the third review, reviewers should also be offering more comments that

- Describe (“In ¶2, you start off with the candidates, but by the end you’re on the media. I don’t understand how you are connecting the details in this section.”)

- Mention the criteria in the review (“The thesis isn’t arguable.”)

- Suggest a strategy or question that moves the writer forward (“Think more about the counter-argument by exploring what people who believe X use as their reasons.”)

- Respect the draft and the writer (“Your passion comes through here, and it helped me see X.”)

Once students are highly consistent with the three moves, then instructors can move on to help reviewers to first detect problems more accurately and then to suggest effective solutions.

Strategy: Ask students to rate the feedback they get for helpfulness.

Teaching students to give and recognize helpful feedback is fundamental for success in peer learning. Eli encourages reviewers to improve through four steps:

- Give helpful feedback as a reviewer

- Get helpful feedback as a writer

- Rate how helpful the feedback was for revision

- Add the best feedback to a revision plan

In the third step, rating helpful feedback, writers rate the comments they received much like consumers rate their purchases on Amazon. The ratings contribute to a reputation system that let students and instructors know who the most helpful reviewers are and which are the most helpful comments. Those exemplars make it easy for instructors to model helpful feedback.

For the reputation system to work well, most comments should get three stars. Three stars out of five is not bad; it’s normal. But, it’s hard for students to get in that mindset.

The student tutorial “Giving Helpful Feedback” explains the criteria of helpful comments to reviewers who are writing them and then to writers who are rating the comments. We encourage reviewers to “describe-evaluate-suggest,” and we encourage writers to rate feedback based those same elements using a checklist like this:

Each “yes” answer is one star:

- Does this comment describe the draft? Does it help the writer understand the draft any better?

- Does this comment evaluate the draft? Does it help the writer measure progress toward the assignment goals?

- Does this comment suggest a revision? Does it offer any specific advice for improvement?

- Does this comment show respect for the draft and the writer?

Add a the fifth star if the comment is extraordinarily helpful.

Instructors can help students put helpfulness ratings in perspective. What three stars means is socially constructed over time as the class develops its own way of evaluating feedback. Figuring out the differences between a three star comment and a 2 star comment and then a 4 star comment will help students be more intentional when the give feedback as well as when they rate it.

Our instructor tutorial “Strategies for Helpfulness Ratings” offers several strategies for helping students become “stingy with the stars”:

- emphasize that helpfulness ratings are the way for writers to ask reviewers and the instructor for better feedback in the next stage

- never tie helpfulness ratings to grades (because students protect their own)

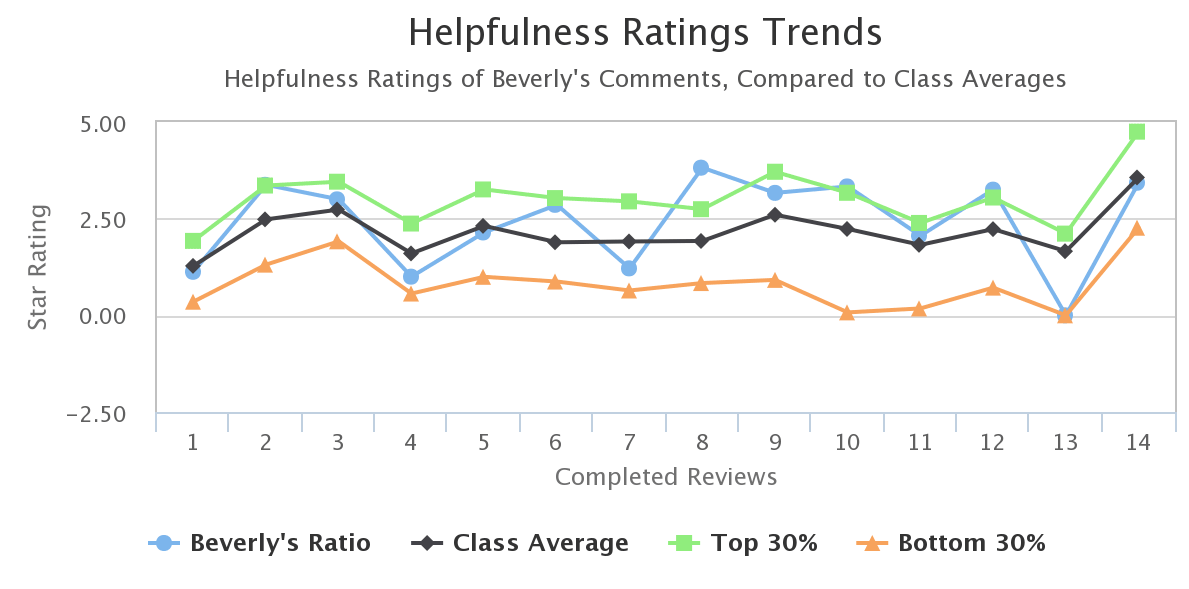

The helpfulness ratings not only reinforce the qualities of helpful feedback but they also create a set of downstream analytics. Class and student-level analytics show instructors how reviewers’ helpfulness changes over time.

Keep in mind that it’s not unusual to see the Helpfulness Rating Trends under Analytics go down. As everyone gets better at giving feedback and as three stars becomes more common, the class average usually dips from its pinnacle at the start of the semester when students were less discriminating. By the end of the term, the average might approach 5 again, but instructors can be more confident that this result reflects improvement, not skew.

Keep in mind that it’s not unusual to see the Helpfulness Rating Trends under Analytics go down. As everyone gets better at giving feedback and as three stars becomes more common, the class average usually dips from its pinnacle at the start of the semester when students were less discriminating. By the end of the term, the average might approach 5 again, but instructors can be more confident that this result reflects improvement, not skew.

After students learn to discriminate helpful feedback using the five star reputation system, helpfulness ratings make it is to see growth in reviewers’ ability to give better feedback.

Strategy: Endorse sparingly and with a clear purpose.

Another way instructors can help students feel confident about the feedback they are giving is to endorse it. Instructor’s celebration of a helpful comment is a strong signal of approval.

Endorsements can be verbal. As part of their debriefing routines, we encourage instructors to coach students by modeling the best comments. Talking to students about why a comment is helpful gives other students a way to improve their feedback next time.

In Eli, endorsements can also be literal. In the app, instructors can give a thumbs up to any comment.

That simple action cues writers to follow the reviewers’ suggestion and gives reviewers a virtual pat on the back.

Our instructor tutorial on “Endorsing Student Feedback” includes recommendations for how to use the thumbs up to encourage better feedback and revision. Endorsements work best when instructors endorse a few comments for a clear purpose. For example, instructors can endorse only those comments that are consistent with the most important goal of the review and that “describe-evaluate-suggest.” Being very discriminating as you endorse makes the endorsement more valuable, and telling students what that endorsement means helps them understand what you value.

Endorsement also creates a digital trail in the analytics that teacher-researchers can use to study helpful reviewers and helpful comments. At the end of the term, if instructors have endorsed sparingly, a student’s cumulative number of endorsed comments is a strong signal of their improvement as a helpful reviewer.

Creating a learning environment where students know how to improve and that they’ve improved is the best way to confront their lack of confidence. Instructors begin by being confident in students. Next they focus on a reasonable goal such as expecting comments to have the three parts: describe, evaluate, suggest. They encourage students to rate the helpfulness of each comment, and they endorse only the best comments.

These strategies help show students by word, deed, and numbers that their effort at giving helpful feedback is paying off. Over time, they’ll gain confidence in giving feedback because they’ve learned how to be helpful by giving, rating, and debriefing a lot of comments. By using routines like “describe-evaluate-suggest” and helpfulness ratings, students get the practice they need to see growth.

Read Part 1 of You've Totally Got This, Developing a Growth Mindset

References

- Dweck, Carol. 2006-2010. “Change Your Mindset: First Steps.” Mindsetonline.com. http://mindsetonline.com/changeyourmindset/firststeps/index.html.

- Bedore, Pamela, and Brian O’Sullivan. 2011. “Addressing Instructor Ambivalence about Peer Review and Self-Assessment.” WPA: Writing Program Administration – Journal of the Council of Writing Program Administrators 34 (2): 11.