This post is a part of the series Challenges and Opportunities in Peer Learning.

In this blog series, we’ve been exploring the design challenges of peer learning. We started with four instructor-side problems:

- Scheduling too little practice without a clear progression;

- Undermining the process by rescuing students with ill-timed expert feedback;

- Distracting students with too many criteria, which muddles evidence of learning; and

- Not talking to students about what they accomplished and still need to accomplish.

We acknowledge that these are reasons for not assigning peer learning, and we don’t name them as excuses. Teaching is hard, and choosing which hard things to attempt is always situated and complex, institutional and personal. As always, our goal in this series is to make it easier to commit to peer learning.

Our next two blog posts focus on the “no pain, no gain” aspect of learning. Developing new skills as thinkers, readers, writers, and reviewers take practice. Yet, nobody loves practice. In this first post, we discuss disengagement in peer learning; in the second, we discuss strategies for keeping everyone engaged.

Design Challenge: Student disengagement has direct effects in peer learning.

The #1 reason teachers tell us that Eli doesn’t work for them has nothing to do with Eli: It’s missing and poor work. Peer learning only works if students are turning in timely drafts and giving helpful feedback.

Now, the same statement could be made of practice tests, reading quizzes, and online personalized learning assessments. Study tools only improve learning if students use them. Of course, this is also true for students who don’t practice math problems or scales on the piano. But it might escape some students’ notice that engagement in peer learning activities demands their attention as much as these individual tasks.

When students don’t do homework, we know there’s a consequence. Students who don’t read before class and then don’t talk in class (or worse yet, do anyway!) are limiting what they can learn. Their disengagement has a direct effect on them and an indirect effect on the rest of the class.

Missing and poor work affects the routines involved in peer learning, however. This is every instructor’s real challenge in peer learning. Individual disengagement has direct effects on other students:

- Prepared writers may not get timely feedback because of late reviewers.

- Helpful reviewers may not get effective feedback because of unhelpful reviewers.

- Late writers hold their reviewers’ progress up because reviewers can’t comment on missing drafts.

Instructors worry that students who do a lot may get little in return. Happily, this is not true. Students who are engaged in giving high-quality feedback benefit a great deal. Yes, you read that right. This post’s references are just a thimble-size portion of the data that shows that students’ own writing improves when they give good feedback, not when they get it. Still, group work can seem risky, which is why it is a perennial topic in publications like Faculty Focus.

At Eli Review, we talk to teachers who back away from rapid feedback and revision cycles because the analytics revealed the extent of student disengagement. They drop peer learning in order to minimize the damage disengaged students have on engaged students and to minimize docking points for a large swathe of students. It’s a tempting response, honestly. I deal with disengagement head on every class period at the community college where I teach. When we can’t count on students to do the work, it’s hard to make peer learning a priority. After a few sessions where a significant portion of the class is disengaged, assigning more peer learning can feel counterproductive for us and our best students.

Design Opportunity: Motivate deliberate practice.

The flipside is this: If students don’t practice giving and receiving feedback in peer learning, is there any reason to expect improvement in their drafts or writing habits? Is there an alternative classroom teaching strategy that works as well as peer learning at improving the paper and the person?

For instructors teaching 4-5 sections of 20-25 students (typical at high schools and at many colleges) or assigning writing to a 100+ student lecture course, we just don’t see a viable alternative that provides as much writing practice as peer learning:

- Jeff Grabill’s Computers & Writing 2016 keynote explained that robots can’t do it, and they represent a threat to core writing instruction values.

- More teacher feedback is often impossible given the current workload and is not always more effective.

- Tutorials like those provided at writing centers or through tutor-led writing groups require an institutional infrastructure to support them.

Effective peer learning experiences improve learning outcomes and professionalize teacher work. Time spent on coaching feedback is time well spent. It is a catalyst for learning and for writing improvement.

Deliberate Practice in Doing What Expert Writers Do

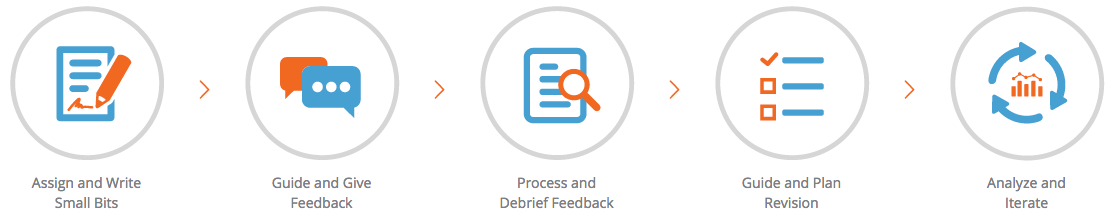

Let’s be clear about what the work of peer learning is. Students compose a text, and then give each other feedback based on questions instructors design to help students bring the criteria into focus. Everyone debriefs, talking through models and trends as a class and, as individuals, rating each comment and deciding whether to add it to a revision plan. Writers plan their revisions and may get instructor feedback before revising the text again. Peer learning helps students do what expert writers do: revise substantially and intentionally.

A good peer learning experience should engage students in deliberate practice (see Ericsson 1993 or Peak) of the skills that lead to the desired outcomes. It should put students in the zone of proximal development with a coach who is using evidence-based methods to guide students toward optimal practice of key skills and reflection on the process. An effective peer learning experience is carefully designed and executed to improve students’ ability to read and write using the criteria that matter most.

Deliberate Practice Isn’t Optional

Since we don’t have a teaching alternative that is as effective as deliberate practice in doing what expert writers do, we have to take student disengagement in giving and using feedback as an indication of a serious learning problem.

If skills and habits are best learned together, students who don’t participate aren’t getting the minimum deliberate practice needed. Students can reject deliberate practice in peer learning for lots of reasons:

- Maybe it’s not clear to them what we want.

- Maybe we’re asking too much, too fast.

- Maybe the reward/punishment isn’t motivating.

- Maybe their lives are too complex.

- Maybe they figured out that they aren’t ready for the kind of practice needed to get better.

These reasons point to a key realization that many teachers make: When it comes to deliberate practice, we have to help students understand the costs and benefits of doing the right amount of work at the right time to see improvement. If they make poor cost/benefit choices, it will hurt their learning.

Practically speaking, it’s easy enough to leave late writers and reviewers behind. A new feature released this summer gives instructors using Eli a way to automatically exclude late writers from review groups and then add writers in as they get back on pace. Everyone gets off pace sometimes. Patterns of disengagement, though, mean that students are not getting what we think they most need to learn.

Practically speaking, it’s easy enough to leave late writers and reviewers behind. A new feature released this summer gives instructors using Eli a way to automatically exclude late writers from review groups and then add writers in as they get back on pace. Everyone gets off pace sometimes. Patterns of disengagement, though, mean that students are not getting what we think they most need to learn.

Bill Hart-Davidson explains the minimum practice needed to improve as the lowest effective dose. The metaphor comes from exercise physiology. Like trainers in a gym, we are looking for the right mix of duration and intensity to cause a meaningful adaptation. We have to help students understand that there is a lowest effective dose in peer learning engagement: no pain, no gain.

Bottom-line: Make peer learning primary.

Defining giving and using peer feedback as “the lowest effective dose” of writing instruction a pretty radical methodology for three reasons:

- Final draft quality is irrelevant. (“Did we have more As?” is not a good question in this approach. Yep, we said it again: Improved final drafts are not the best proof that learning happened. Good final drafts are fun to see. But they may be poor indicators of student learning.)

- Incoming student quality is irrelevant. The focus is on what students do as reviewers and as writers in revision plans, not merely their performance levels. We won’t see a ceiling effect here where strong writers at the start grow very little across the span of 16 weeks. The wonderful side effect of building a feedback-rich classroom is that your best writers can improve as much as anyone else. Focusing on behaviors also means we won’t see weak writers grow a lot but still fall short of the desired proficiency.

- Only actions are relevant when instructors trust the evidence that peer interaction is a driver for learning. If students don’t engage in giving and using comments, that’s a clear pedagogical design problem: What kept students from the effective dose?

At Eli, we’ve made giving and using feedback the primary mode of learning. We’ve haven’t found a silver bullet against student disengagement, but we have made two turns in our practice:

- We do everything (planning, class time, grading) assuming peer learning is the best experience we can offer our students.

- We assume that students’ growth depends on deliberate practice alongside their peers.

These beliefs shape every part of the courses we teach: assignments, lesson plans, grading schemes, even how we comment on student work.

These beliefs are evidence-driven and apply to the time students spend in our classrooms. But, they are is even more true for students once they leave our classrooms. Helping students become good peer learners is the best way to give them the tools to keep learning throughout their careers.

Check out Part 2 of No Pain, No Gain, Keeping Everyone Engaged, coming on 10/13

References

- Ericsson, K. Anders, Ralf T. Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Römer. 1993. “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance.” Psychological Review 100 (3): 363–406. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363.

- Ericsson, K. Anders. 2016. Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Thimble of Empirical Research on Value of Giving Feedback. Bloxham, S., and A. West. 2004. “Understanding the Rules of the Game: Marking Peer Assessment as a Medium for Developing Students’ Conceptions of Assessment.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 29 (6): 721–733.

- Cho, Kwangsu, and Charles MacArthur. 2011. “Learning by Reviewing.” Journal of Educational Psychology 103 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1037/a0021950.

- Li, L., X. Liu, and A. L. Steckelberg. 2010. “Assessor or Assessee: How Student Learning Improves by Giving and Receiving Peer Feedback.” British Journal of Educational Technology 41 (3): 525–536.

- Cartney, P. 2010. “Exploring the Use of Peer Assessment as a Vehicle for Closing the Gap between Feedback Given and Feedback Used.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (5): 551–564.