This post is a part of the series Challenges and Opportunities in Peer Learning.

This blog series on the design challenges and opportunities in peer learning emphasizes ways instructors can create feedback-rich environments that help them see students’ learning in time to intervene before grading. Small bits of writing with targeted criteria help everyone zero in on the most important learning indicators. When the questions direct reviewers’ attention to the critical skills, instructors have some confidence that peer feedback will provide writers with a helpful map of necessary revisions. In this way, an instructor’s first and most important intervention is the peer learning task itself.

The second intervention is debriefing, and its aim is to make sure students don’t miss a key implication of the feedback they personally received or of the feedback exchanged in other groups.

When instructors debrief a peer learning activity, they help students be more engaged in a feedback-rich classroom. In part one of this blog post, we framed debriefing as a method for cognitive apprenticeship. Instructors as expert learners give students a tour of the trends and exemplars from a peer learning activity, talking through strengths, weaknesses, and next steps. Here, in part two, we will offer four strategies for creating an effective debriefing.

Part 2: Reconnaissance and Debriefing

When debriefing, instructors speak to students as expert learners, but they prepare for that conversation as expert teachers. In a previous post, we noted that expert teachers are really good at recognizing when learning is happening. In a face-to-face discussion setting, the signals that learning is happening are eye-contact, answering questions, and asking questions. Expert teachers are really adept at managing the engagement of all learners, and they cut through the noise of off-task behaviors and blank faces. These expert teachers distinguish between signals and noise as well as draw appropriate conclusions from those signals about who needs help. Those reconnaissance skills of gathering information about engagement and drawing conclusions about learning are harder to apply in a peer learning activity because of the sheer volume of interactions. In this post, we offer strategies for learning to get the lay of the land in a peer learning activity in the same way that instructors take the pulse of a class in discussion.

Up front, we want to underscore that gathering evidence in peer learning and debriefing important trends with students is evidence-based teaching that takes practice and builds expertise. Eli was designed to develop this kind of teacher expertise around formative feedback in situations where writing is the primary mode for learning. Eli is unique in how it displays, connects, and exports students’ work in drafts, comments, and revision plans. Those features were designed to make it possible for instructors to read and interpret what is essentially a transcript of students’ work in peer learning.

In this way, instructors can use Eli to develop expertise in understanding how learning unfolds for differents students. As reflective practitioners, instructors interpret the evidence to know how effective their teaching is:

- Did I prepare students well for this activity?

- Did they understand my instructions?

- What kept students from meeting my criteria?

- Which needs did I miss in preparing them for this task?

Questions like these are the heart of all formative feedback. The NCTE position statement “Formative Assessment that Truly Informs Instruction” explains:

Formative assessment is the lived, daily embodiment of a teacher’s desire to refine practice based on a keener understanding of current levels of student performance, undergirded by the teacher’s knowledge of possible paths of student development within the discipline and of pedagogies that support such development. (emphasis ours)

Debriefing is as much for instructors as it is for students. As they prepare to talk to students about their learning, instructors get closer to students’ needs, their language, and their growth.

Developing a Reconnaissance and Debriefing Routine in Eli

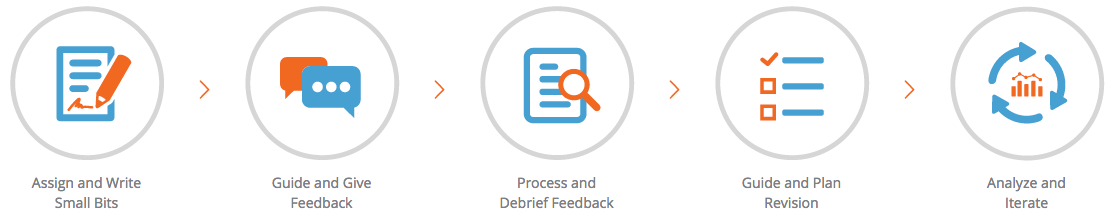

Eli was designed to make it easier to see students’ thinking and thus easier to talk about better thinking. When instructors ask for smaller bits of writing and guide students in giving feedback according to targeted criteria, they open up a space to talk about how learning that one thing happened or didn’t happen as the activity wraps up. Eli makes that conversation easier because the activity itself should be clear signal of learning, not a noisy one. Eli also makes it easy because instructors have real-time access to all exchanged drafts and comments. The image below shows that “process and debrief” is the third stage of the peer learning workflow:

When students “process feedback,” writers rate comments for helpfulness and add comments to revision plans. These actions help instructors know if students have gotten what they needed from the peer learning activity.

Debriefing usually follows these choices by writers. Debriefing is conversation (or video or email or uploaded report file) that looks backward over all the work students have done as writers and reviewers and then looks forward to the work they need to in revision. Helping students understand the thinking and steps behind success is much easier when instructors can see what students can do as writers and what they can say to each other as reviewers.

In our work with instructors over the past four years, we’ve learned that developing a routine of reconnaissance and debriefing can be a challenging. Debriefing boils down to four strategies:

- See as much as you can.

- Discuss pertinent results with whole class

- Intervene with individual students

- Plan the next peer learning activity

The strategies are easy, but the data is deep. With practice, instructors recognize more patterns and can more easily distinguish signals from noise. By the third debriefing session, instructors are beginning to find their voices—how they’ll frame the trends, discuss exemplars, and redirect less helpful comments. In the sections below, we offer guidance for each strategy.

Strategy: See as much as you can.

The first strategy is reconnaissance. Instructors should see as much as they can in the peer learning activity. Jeff Grabill says, “You can’t teach what you can’t see.”

When instructors are trying to provide students with a cognitive apprenticeship, that line has several implications for debriefing:

- If you can’t see your own process, you can’t teach it to students.

- If you can’t see what students can do well, you can’t push them to the next level.

- If you can’t see why students are struggling, you can’t help them succeed.

- If you can’t see who needs extra help, you can’t provide it.

Eli’s approach is to put the data from students’ work in drafts, comments, and revision plans at instructors’ fingertips—on screen in the app or in .csv downloads—so that they can talk to students from the evidence.

For many instructors, reading students’ work in this way is a new and overwhelming experience. Our advice is to focus on the most important thing. Eli captures everything, but no one can teach everything at once, just as no learner can learn everything at once. Read to find the big trends that move everyone one step closer to the goal.

In our professional development module on evidence-based teaching, we describe this work as reading the data in order to

- “sweep across the line” in order to say back to the class how everyone is doing,

- “lean out” and let students struggle a bit, or

- “lean in” to intervene.

As they read students’ drafts, comments, and plans, instructors are deciding to focus learners’ attention next. “Sweeping across the line” helps establish the peer norm and the acceptable level of performance. This narrative of where the class is helps students build confidence that they understand the expectations. “Leaning out” is one of the arts of restraint where instructors choose to keep learners focused on other things and to trust the process rather than directly address problems. By contrast, “leaning in” is when instructors decide that a trend merits direct intervention, either with the whole class or with an individual student.

The goal of wading through the data from peer activities is see is to see learning and develop observations. Some observations help describe the desired performance. Some are silenced in favor of keeping attention elsewhere. Some are used to redirect effort.

Strategy: Discuss pertinent results with whole class.

Once they develop the observations that are most pertinent, instructors talk to students about the implications. This is debriefing as a report or a conversation. Because of the data Eli captures, instructors can debrief in several ways:

- Debrief with writers to inspire revision

- Trends in Trait Identification checklists

- Models from Star Ratings

- Trends in Helpful/Endorsed Comments

- Debrief with reviewers to inspire better feedback

- Peer norms in effort (quantity of comments, helpfulness ratings)

- Models of helpful comments

In this assignment sequence, students’ work as writers and as reviewers becomes a primary text in the class. Instructors mine and interpret that primary text from students’ work in order to find the signals that learning is happening; once trends and models are identified, instructors can talk students through them.

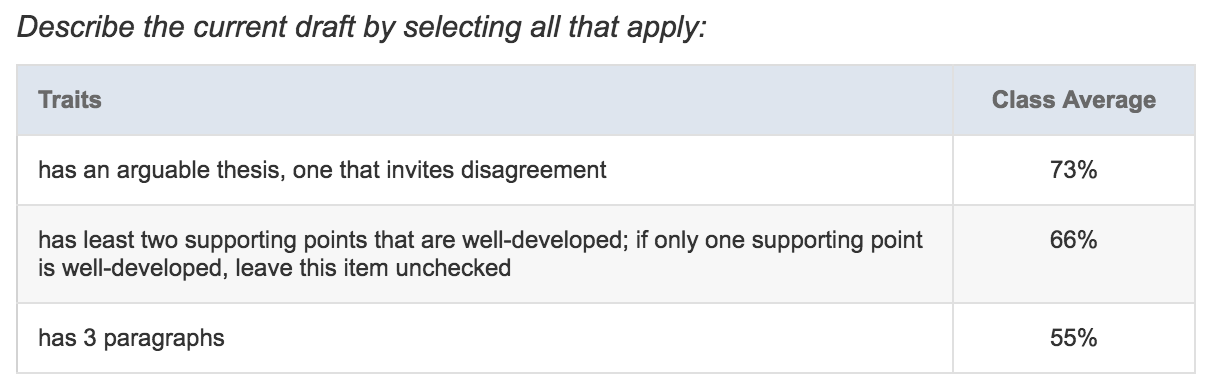

Instructors who have experience running writing workshops are on familiar ground when using Eli’s “Writing Feedback” tab to talk with writers about the trends in their drafts. Because the review task is designed like a survey, the results make it easy for instructors to sweep across the line. They can talk with students about any percentage that seems too high or too low.

Most instructors find working closely with students’ comments to be unfamiliar territory. In other technologies like Microsoft Word or peer grading apps, comments aren’t aggregated and are deleted as soon as a writer works through them. By contrast, Eli treats comments as an authentic record of learning. What students can say to each other about their work is really strong signal of learning. Eli displays comments in several ways, inviting instructors to model helpful comments, endorse them, and even research them. In the video below, Elon University professor Jessie L. Moore discusses how spending more time talking about good and weak comments changed her teaching and improved students’ learning.

By discussing with students the qualities of helpful comments, Jessie tries to make sure that students are well-prepared to give better feedback next time.

Debriefing with writers about revisions and with reviewers about helpful comments reminds students that the peer learning activity kept them busy doing the important work of learning. It’s not just busy work.

Strategy: Intervene with individual students.

In this series, we’ve described coaching peer learning as a long lever and instructor feedback as a short lever. With the long lever, instructors read through the data and discuss results in a debriefing conversation with the whole class. Often, reading through the data surfaces students who need extra attention, and instructors can pull out that short lever and respond only to the handful of students who need it. This is one of the time-savers of being an evidence-based teacher: You can see who is stuck.

Here are some ways to identify struggling students in Eli:

- Writers with low percentages in trait identification checklists or low averages in ratings may not understand how to meet the expectations of the assignment.

- Look through the individual writer report in the review task by click on the student’s name and then reading the “Feedback Received” tab.

- If revision plans are assigned, the instructor note is the perfect place to help the writer get on track.

- Late writers are unprepared to give feedback and get it.

- Find late writers in the “edit groups” option in a review task–they have an icon of a sheet of paper with a red x beside their names.

- Figure out if students just had a hard time meeting the deadline or if writer’s block is at work.

- Reviewers offering few comments or short comments may not know what to say to other writers and so may be struggling with how to think about their own work.

- Use the “Engagement” tab in a review task to sort reviewers by “Comments Given.” Or, download the comment digest and use a pivot table to summarize reviewers’ comment length.

- Teach students to write more and longer comments by regularly showing models of helpful comments. Consider using our resources for “describe-evaluate-suggest.”

- Unhelpful reviewers (those whose comments are rated below 3 stars for helpfulness) may not understand why their comments aren’t leading to revision.

- Use the “see all comment ratings from all reviewers” option in the Review Feedback tab in a review task to see the class roster sorted from most to least helpful reviewers.

- Read through the comments and decide how to motivate reviewers to give better feedback. Again, our resources for “describe-evaluate-suggest” may be useful.

In each of these conversations, the goal is to help students figure out what’s next to get them back on track.

Strategy: Plan the next peer learning activity.

Combing through the data and talking about observations to the class and individual students gives instructors a clear and nuanced view of student learning. With that picture in mind, instructors can decide what the next small bit and targeted feedback will be.

Bottom-line: Debriefing helps instructors and students build expertise.

Studying students’ work as writers and reviewers helps instructors make sense of learning. Through this process, we become more expert teachers. Saying aloud what we think about a draft or a comment helps students learn how we think. We help students become more expert learners.

We assign peer learning activities because studying students’ work and debriefing it helps us do something that is really hard: It helps us be clear about a process that is routine to us but opaque to novices. The work we do to tell students our observations makes us better teachers and leads to better learning. Don’t miss the chance to debrief.