This post is a part of the series Challenges and Opportunities in Peer Learning.

“Your students aren’t revising enough” – that’s what Bill Hart-Davidson tells the teachers he works with when he sees just one review for each assignment in a writing course. Revising, he says, is the most important skill a writer needs to learn, and we as teachers must provide them with the opportunity to practice it:

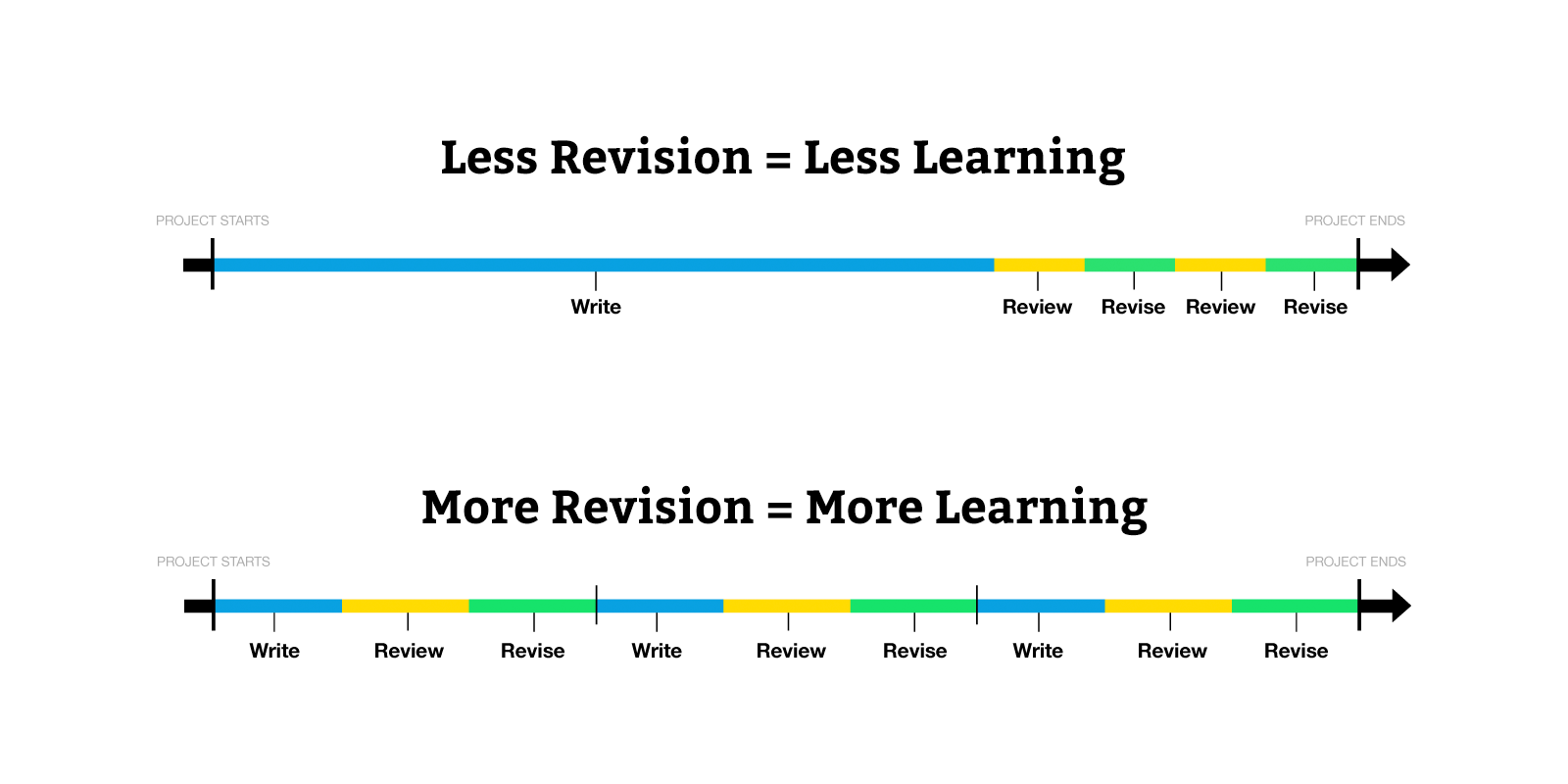

The greatest risk in your class is that students will not practice enough of the right skills at the right time to learn. Let me say that again: Your greatest risk as a teacher is assigning too little, poorly sequenced practice. With too little practice, the greatest risk is your students won’t learn.

This blog series addresses the design challenges instructors face in creating the kinds of peer learning environments that drive effective revision practice. Those dilemmas feel familiar: finding the time, motivating students, worrying that they have the skills to help each other learn. But, we of the Eli Review team— Jeff Grabill, Bill Hart-Davidson, Mike McLeod, and Melissa Graham Meeks—approach these dilemmas from what might be an unfamiliar place. We understand more peer learning, done well, as the solution to motivation, skill development, and learning. In the classes we teach and in our work as a company, peer learning is routine and powerful.

Design Challenge: Peer learning is too rare and often ineffective.

Our conversations with instructors at every level have underscored that peer learning is too rare and often ineffective. They see peer learning as risky because, for example, students are likely to give bad feedback. Of course they do when they start! That’s THE teachable moment. When students don’t know how to talk to each other about their work, they don’t have the knowledge or skills needed to improve even their own. Let’s put this differently. ONLY when students can talk about their work do we know that they have developed new knowledge and skills.

Design Opportunity: Sequence the skills; schedule the practice.

Our job as teachers is to sequence the skills and schedule the practice so that students have the best chance to learn.

Designing the right practice at the right time means understanding how students learn the skills and material in our classes.

Strategy: Create conditions where students think.

In the American Educator article “Why Don’t Students Like School?” that summarizes his book of the same name, Daniel Willingham grounds his recommendations for designing successful learning environments in this cognitive principle:

People are naturally curious, but they are not naturally good thinkers; unless the cognitive conditions are right, people will avoid thinking. . . . Compared with your ability to see and move, thinking is slow, effortful, and uncertain. (4-5)

Teaching is helping students do slow, effortful, uncertain thinking. Willingham points out that people need a problem that they are curious enough to solve as well as the background knowledge and working memory to solve it; he also emphasizes the “burst of pleasure” people get from solving problems (7). In his view, learners need solvable puzzles, clear scaffolding, and tangible results that make them feel good.

Strategy: Commit to peer learning.

Willingham’s work in cognitive psychology echoes the work of other great teachers like Ken Bain (What the Best College Teachers Do), Linda Nelson (Teaching At Its Best), and Ambrose et al. (How Learning Works). These teacher-researchers call for engaging students in doing something alongside other learners while being coached by an expert learner.

As writing teachers, we also hear echoes of Don Murray in “Teach Writing as Process Not Product” who asked and answered this key question about deliberate practice:

How do you motivate your student to pass through this process, perhaps even pass through it again and again on the same piece of writing?

First by shutting up. When you are talking he isn’t writing. And you don’t learn a process by talking about it, but by doing it. Next by placing the opportunity for discovery in your student’s hands. When you give him an assignment you tell him what to say and how to say it, and thereby cheat your student of the opportunity to learn the process of discovery we call writing. (3)

Murray’s list of ten implications for process pedagogy in composition classrooms still resonates, reminding us of the patience needed to come alongside inexperienced writers as they grapple with confidence and competence.

Peer learning puts students in Murray’s discovery mode most often. It’s especially powerful when the activity follows Willingham’s suggestions for helping students find pleasure through “slow, effortful, and uncertain thinking.” Surrounded by peers, guided by an instructor, and immersed in feedback, peer learning is more likely to help students improve than any other method.

Strategy: No, really commit to peer learning.

Because peer learning gives us a chance to create the optimal conditions for thinking, the greatest risk is not assigning enough of it. In Small Teaching, James L. Lang says,

The implications [of Willingham’s work] are clear enough and articulated already: whatever specific cognitive skills you want your student to develop, they should have multiple opportunities to practice beforehand. (121)

Our course calendars are arguments for what skills students should practice, and peer learning is our most productive practice. The schedule helps students to see how much and how often they should practice if they expect to improve.

As a company, we have data suggesting that courses including 5+ reviews are giving students enough practice to be able to expect better feedback and revision. As teachers, we often assign 10+ reviews per course, around once a week. There isn’t a magic number. The total number matters, though.

Strategy: Peer feedback tells you what students don’t know.

To make sure the practice is productive, we embrace Mina Shaughnessy’s insight in Errors & Expectations that students’ mistakes are helpful feedback for teachers. When students fail to give good feedback, the solution is not to step in and assume control; the solution is to help students work through the challenge to make new connections and, eventually, gain fluency. Reviewers who can reason their way into giving better feedback can likely reason their way into a revised draft too.

Bottom-line: Every common problem of peer learning is an opportunity for improving learning.

To make peer learning successful, instructors need to stop thinking of peer learning’s common problems as disadvantages. The likelihood that some students will give unhelpful feedback and some will heed it is not a risk. It’s not a reason to skip peer learning in favor of another method. Unhelpful peer feedback is a design challenge, just as timing, motivation, and skill development are design challenges. Peer learning has common problems because the struggle to stand alongside novice learners is similar across disciplines and contexts. We should design for these considerations*, not skip peer learning because of them. To get the best results from peer learning, instructors need a learning design repertoire that helps them know:

- when to shut up

- how to know what students don’t know

- when to say more

- who to call out

- who to encourage

- how to address resistance

- how to use peer norms

For the next two months, we’ll release a blog post about each of the above design challenges, reframing them as opportunities for instructors to create a rich peer learning environment—one with enough practice of the right skills at the right times.

* For this list of considerations, we are indebted to the cross-disciplinary inquiry group called “Helping Students Become Better Writers and Better Responders” coordinated by Heidi Estrem at Boise State University. In May 2016, Heidi and I [Melissa Meeks] collaborated on a full-day workshop to kick off a year long conversation with faculty from Health Sciences, Material Sciences, Information Technology, Business, English Education, and English. We started by framing our prior experiences of facilitating peer learning in light of Dylan William’s “The Secret of Effective Feedback” and E. Shelley Reid’s “Peer Review: Successful from the Start.” That excavation work yielded this list and inspired this series. The Eli team is grateful for the opportunity to partner with the Boise State group, and we look forward to all the things we’ll learn together.

References

- Ambrose, Susan A., ed. 2010. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. 1st ed. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bain, Ken. 2004. What the Best College Teachers Do. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Lang, James M. 2016. Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer.

- Murray, Donald Morison, Thomas Newkirk, and Lisa C. Miller. 2009. The Essential Don Murray: Lessons from America’s Greatest Writing Teacher. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers/Heinemann. (Web Sample)

- Nilson, Linda Burzotta. 2010. Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based Resource for College Instructors. 3rd ed. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Reid, E. Shelley. 2006. “Peer Review: Successful from the Start.” The Teaching Professor 20 (8): 3.

- Shaughnessy, Mina P. 1979. Errors and Expectations: A Guide for the Teacher of Basic Writing. 2. printing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- William, Dylan. 2016. “The Secret of Effective Feedback.” Educational Leadership 73 (7): 10–15.

- Willingham, Daniel. 2009. “Why Don’t Students Like School? Because the Mind Is Not Designed for Thinking.” American Educator, no. Spring 2009: 4–13.