For the past two years, several high school teachers have been teaching writing differently. Through the Statewide Writing Research Project, 30 teacher-researchers and 1,400 students in the Oakland ISD have been working with Michigan State’s WIDE program to answer one question: “How do we teach effective writing and revision?”

As part of their on-going action research projects, teachers at Avondale, Clarkston, Oak Park, and Royal Oak have been developing strategies for teaching students to give high-quality formative feedback. Recently, they reported on their experiences to the district, and this article highlights student successes and teaching strategies.

Students Give High-Quality Feedback

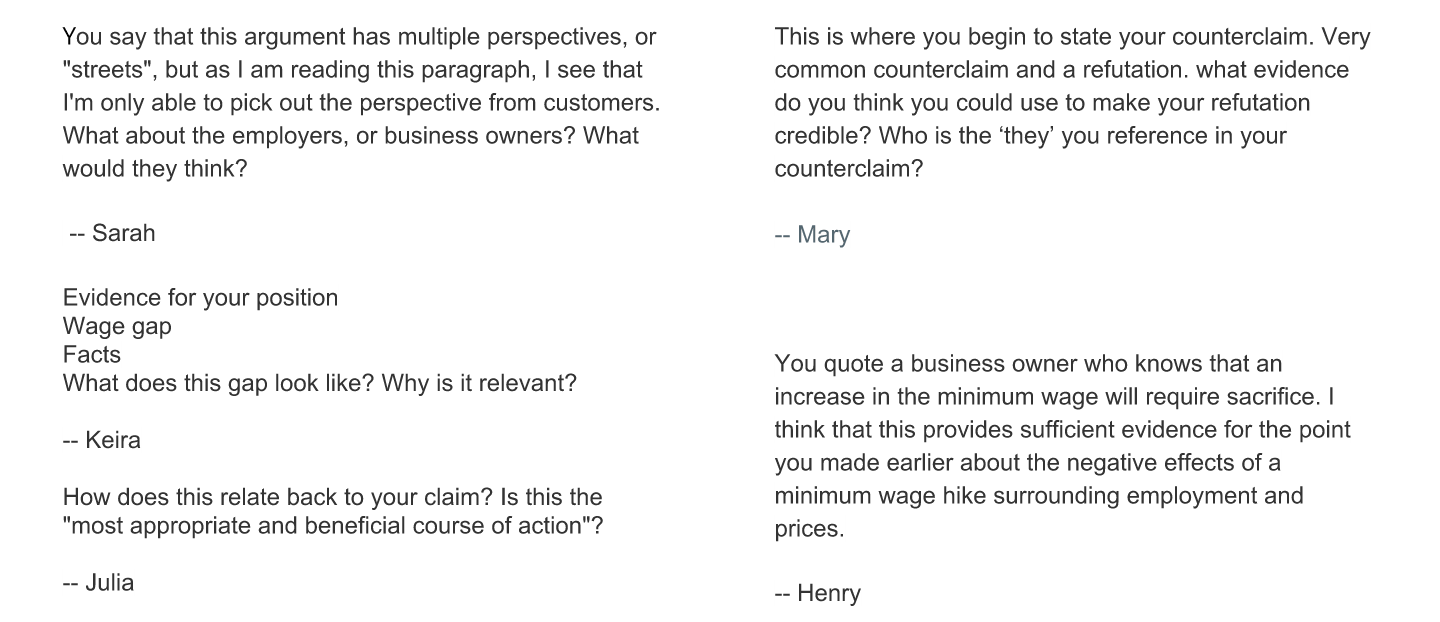

Teachers focused on the ways students are now talking to each other about writing. Instead of giving praise and marking a few typos, reviewers respond to writer’s ideas and connect their advice to the higher order expectations for the assignments. This slide shows five examples from Derek Miller’s 11th Grade AP Language and Composition class at Royal Oak High School in which reviewers tell writers why more perspectives, evidence, and counterarguments are needed at specific parts in their drafts:

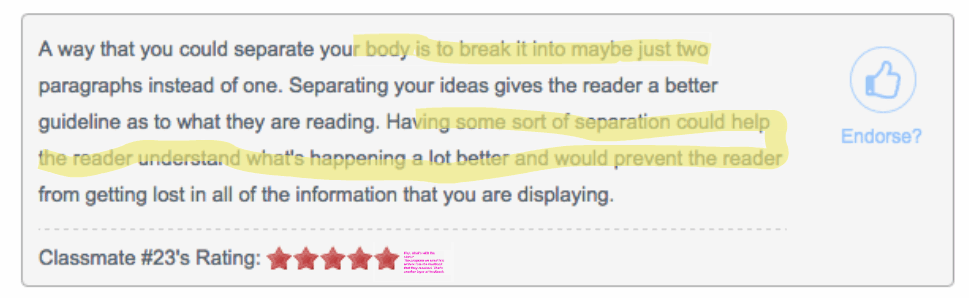

Reading drafts in order to say back to writers what they understand about claims and evidence also helps students notice issues of organization. Avondale High School students in Richard Kreinbring’s class offered these comments:

Because they are taught how to give feedback and because they practice giving feedback orally and in writing most class days, students gain confidence in their abilities. Get a peek into how Derek Miller frames feedback and sets up the activities where students practice their skills and see how his students from Royal Oak High School reflect on how they became confident peer reviewers who can work with the writer’s ideas:

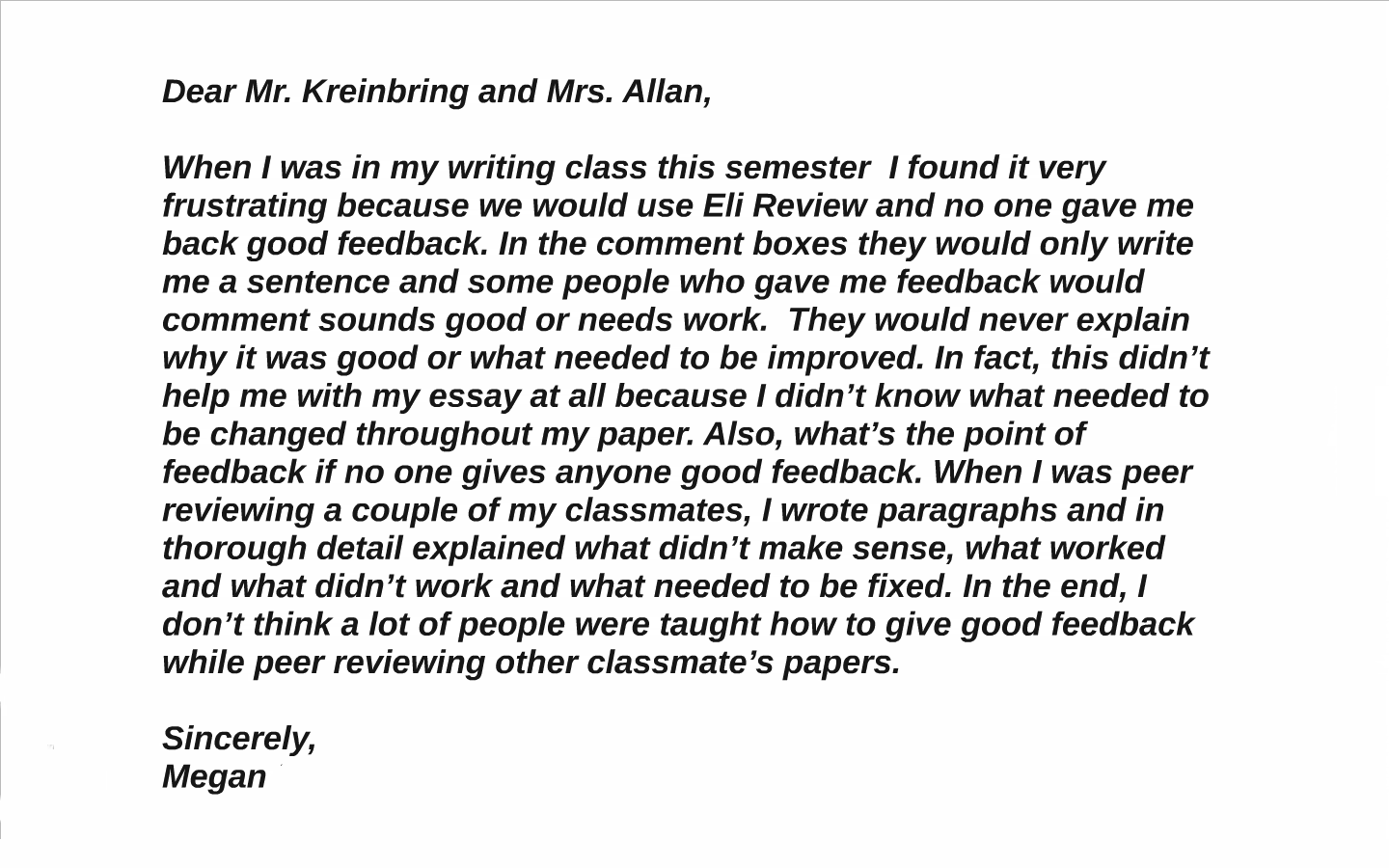

Across all classrooms and schools, students are learning to invest more in giving feedback and to expect more from peer review. One of Richard Kreinbring’s students even wrote back to him to complain about a college class where peers hadn’t been taught to describe what’s working and not working in drafts!

Teachers Share High-Impact Teaching Strategies

Getting students deeply engaged in talking about their writing takes a concerted, sustained effort. Peter Huan, Katie Locano, and Sarah Weaver at Oak Park High School meet everyday to figure out how to help students get the most out of class time.

In fact, instructors across the Oakland ISD expressed how much they focus on giving feedback orally and in writing. It seems a subtle shift; but in practice, it’s seismic. Derek Miller boldly asserts that reviewers’ comments have become the performance record he values most:

“I’ve realized I don’t care about the growth showing in their writing. That’s a side note I think it does, but I don’t care much about it. . . . [Instead, I’m pursuing questions like: If artifacts of peer review demonstrate students are thinking about writing, can I track student learning through feedback?”

By thinking of feedback as a performance record of students’ learning, teachers developed successful strategies for getting students to show their learning in the comments they gave each other.

1. Define effective feedback.

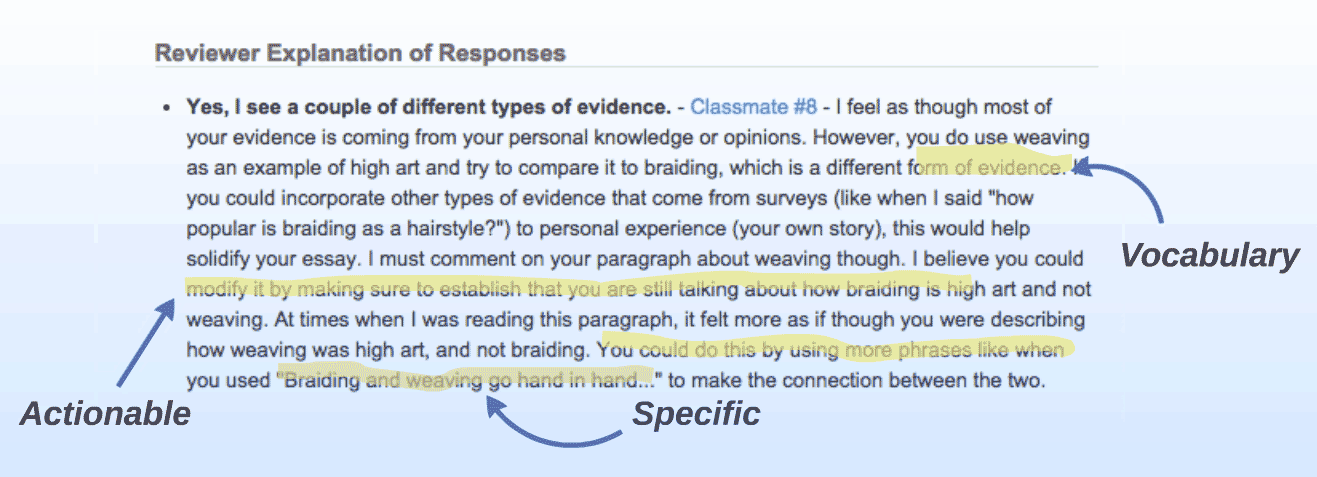

Teaching teams developed their own definitions of effective feedback. For example, in 11th grade ELA Peter Haun, Katie Locano and Saran Weaver used “clear, specific, and respectful.” Kreinbring taught his students to be “specific, actionable, and timely, with a bonus for using vocabulary specific to the discipline.” Derek Miller coached his students to offer “nonjudgmental data and reflective questions,” following Costa and Garmston’s advice in “Supporting Self-Directed Learners.” For these teachers, the definition of effective feedback structures all of the activities around giving feedback and evaluating feedback.

2. Model effective feedback relentlessly.

Teachers had multiple ways to show students why feedback was effective or not effective using the definitions. Richard Kreinbring visually annotated students’ comments so that they could see how the definition of effective feedback applied.

For each instructor, a new review task began by looking back at the success and struggles in the previous review. Using a “we do, they do (turn-talk), and I do” sequence, Peter Haun, Katie Locano, and Sarah Weaver helped students work with six examples–effective and not effective–before they started giving feedback again. Six examples.

3. Emphasize feedback as a way of building community.

Using (online) written and (face-to-face) verbal feedback, these teachers immersed students in talking about their drafts. Immersion wasn’t enough, though. They also had to actively create a “conducive culture” (Huan, Locano, Weaver). Derek Miller explained it this way:

We create the conditions for good conversations about writing in our classrooms. . . The idea of that learning to improve one’s writing is part of a social contract, if you will, is not one all kids take to easily. Some students define themselves by their comparative excellence, the mastery they maintain over their peers. At a certain level, though, it doesn’t matter how smart you are if you can’t get others to relate to your ideas. The inverse of this is the person who is not all that smart but very good at relating to and manipulating his audience. Teaching students to transform their view of writing from self expression to community conversation is a way, I hope, of addressing social responsibility in our society.

These teachers took seriously their responsibilities for creating a safe space for students to negotiate the challenges of effective communication and build each other up as they improve.

4. Encourage students to take ownership.

Shifting how students think about their responsibilities to each other helps them buy into the peer learning process. As Clarkston High School teacher Laura Mahler said, students become “agented learners.” They see themselves as contributing meaningfully to other writers’ development. As Derek Miller points out, students take ownership over the process.

Caption: Derek Miller emphasizes that students’ motivation for giving helpful feedback stems from their sense of ownership over the process.

5. Track reviewers’ helpfulness on a growth curve.

Using a developmental continuum begun by Susan Golab and elaborated by Derek Miller, instructors assess students’ proficiency in response and reflection. Teachers work from the notion that reviewers get better at giving feedback along a predictable path just as readers develop skills along a predictable path. They look at reviewers’ comments to map their proficiency in responding to writing and reflecting on feedback.

How Reviewers Level Up In Talking About Writing

Developed by Susan Golab, Derek Miller, and Melissa Graham Meeks, this rubric shows how feedback evolves.

| Level | Description | Leveling Up |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acting primarily as copyeditors, reviewers label parts of draft, correct mistakes, and/or offer opinions not clearly related to writers’ purposes. |

|

| 2 | As partners in meaning-making, reviewers help writers reshape claims and evidence. Reviewers accurately restate writers’ purposes and ideas, identify strengths, and recommend strategies for improving weaknesses. |

|

| 3 | Relying heavily on instructor’s guidelines, reviewers offer writers meaningful revision suggestions. Reviewers align feedback to criteria. They may occasionally misidentify parts of the draft or misevaluate how well the draft meets expectations. Their comments may restate criteria and often repeat the same suggestions. |

|

| 4 | As fellow writers, reviewers help peers understand how their choices affect readers. They consistently and accurately identify parts of the draft and evaluate how well the draft meets expectations. They ask writers thoughtful questions that often go beyond the instructor’s guidelines. They offer suggestions that reveal a developing awareness of how writers achieve a particular voice. |

|

| 5 | Working as developmental editors, reviewers help writers identify and polish their core ideas through rigorous attention to audience, purpose, claims, evidence, organization, and style. Comments consistently go beyond the instructor’s guidelines. Reviewers help writers productively address the complex rhetorical situation. |

|

These teachers are doing something different. They are treating comments as artifacts of learning that are just as valuable as—maybe more valuable than—final drafts. By paying attention to the words and moves students use when giving other writers feedback, teachers attend to the ways in which students think like expert writers. They’re coaching the thinking between drafts.

Inspired by these great teachers? Learn more about their work in Oakland ISD through the Michigan Statewide Writing Project :

- Susan Golab. Developmental Continuum of Peer Feedback, Accessed February 4, 2016, http://www.oaklandschoolsliteracy.org/argument-writing-

learning-progression/developmental-continuum-of-peer-feedback/. - Peter Haun, Katherine Locano, and Sarah Weaver. Creating a Conducive Culture (Prezi), January 26, 2016, https://prezi.com/pudjbmfengbm/creating-a-conducive-culture/.

- Peter Haun, Katie Locano, Sarah Weaver, and Laura Gonzales. “Digital Writing does not Begin with “the Digital”: Building Cultures of Feedback to Support Effective Writing and Revision,” Digital Rhetoric Collaborative (blog), September 22, 2015, http://www.digitalrhetoriccollaborative.org/2015/09/22/digital-writing-does-not-begin-with-the-digital-building-cultures-of-feedback-to-support-effective-writing-and-revision/.

- Richard Kreinbring, Derek Miller, and Laura Mahler. MCTE Feedback Presentation (Prezi), January 27, 2016, https://prezi.com/vktxkv3juwt9/mcte/.

- Derek Miller. Peer Review and Feedback . . . Or How I Learned All The Thinks I’d Been Told Were True (Google Slides), Accessed January 30, 2016, https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/13TsIZVyd7-S1vAIbl5EO3B7IK0p_AqKKoO-34mq6iyY/edit?usp=sharing.

- Derek Miller. Revised Feedback Continuum (Google Document), Accessed January 30, 2016, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1yLb8O7voJWNYEpUsJ9kJfac2UBcNWWui5MLrNh6FIOM/edit.

See more footage from Derek Miller’s class at Royal Oak High School:

- Clip #1 http://video.oakland.k12.mi.us/show?video=6c9d4bb5d629

3:14 Two students talk about giving feedback, their feedback practices, and support from their teacher. - Clips#2 http://video.oakland.k12.mi.us/show?video=db2f170ba6e9

14:35 Derek Miller talks students through a peer review activity in Eli Review. - Clip #3 http://video.oakland.k12.mi.us/show?video=d4f9fb5956c4

5:33 Two students talk through their written comments and discuss revision priorities. - Clip #4 http://video.oakland.k12.mi.us/show?video=686e3538011d

2:40 Derek Miller coaches students about how to use one good reflective question to consider multiple revision choices. - Clip #5 http://video.oakland.k12.mi.us/show?video=ec883783f7dc

2:15 Derek Miller talks about the challenges of teaching reviewers to pose reflective questions in their feedback rather than giving advice.