This post originally appeared on Bill Hart-Davidson‘s blog for his course Teaching with Technology (AL 841).

Recently, I traveled to Washington State University to talk with faculty there about writing, learning to write, and what the evidence says is the best way to encourage student learning. You can find lots of the material for both the full-day workshop and my University address on the Multimodal blog published by the Writing Program.

In my talk, I reviewed some of the powerful evidence that shows what works in writing instruction: deliberate practice, guided by an expert (teacher), and scaffolded by peer feedback (Kellogg & Whiteford, 2009). But I also urged teachers to be guided by the kind of evidence that emerges from their own classrooms when students share their work. This is not simply doing what peer-reviewed studies say works, but involves systematically evaluating what the students in your classroom need and responding to that as well.

This can be a challenge to do. The evidence we need to make good pedagogical choices for the whole group, or to tailor feedback for a particular student, does not collect itself.

This is why we built Eli! With Eli, instructors can gather information shared by students during a peer review session to learn how the group – and how each individual student – is doing relative to the learning goals for a particular project or for the course as a whole.

A Review Report in Eli

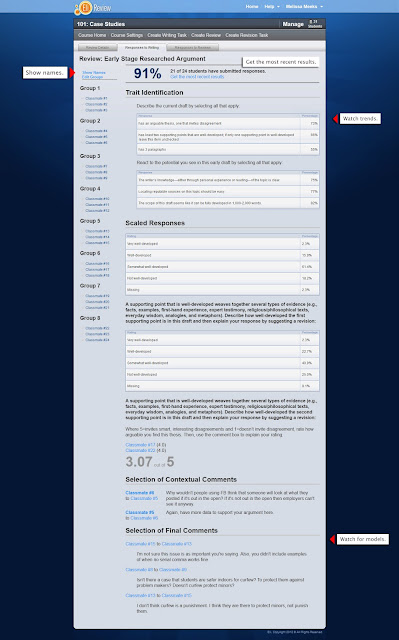

Our marketing partner, Bedford St. Martin’s, has put together some great resources designed to help instructors get the most out of Eli. And one especially helpful discussion that I’d like to point out here shows what evidence a review report makes available and how it might be used to guide deliberate practice in writing. Here’s what a teacher’s review report looks like in Eli:

Because Eli aggregates the results of review feedback into one report, a teacher can see trends that are helpful for providing various kinds of feedback to students. Here, I’ll talk about just one kind of feedback – trait matching – and how it can be useful in the context of deliberate practice. I’ll also offer some examples from my own pedagogy to show why having evidence is so powerful.

Help Students Identify Revision Priorities by Noting Missing Traits or Qualities

One type of feedback that students can give one another is called “trait matching” in Eli. Reviewers check boxes to indicate whether a specific feature is present in the draft. When I’m teaching, I use trait matching items to help students zero in on what is most important at a particular stage in their drafting process. Early on, for instance, it might be a main idea or thesis. Later on, it might be supporting details to develop an argument more fully.

In the review report, then, I get a result like this:

This tells me what percentage of reviewed drafts contained the four traits I have specified should be in each one. Notice that in this summary, most writers have included a summary of their own media use patterns. But fewer writers have made references to two secondary sources in these drafts.

This helps me to identify what I need to emphasize to the whole group, and it also allows me to evaluate each individual student’s revision priorities as reflected in their revision plans (also in Eli). I know that at least 44% of those plans should list references to secondary sources!

Here’s how I might convey these trends to students. First, I will reassure them that the patterns they’ve noticed agree with my own reading of their work. This let’s them know that they can trust the feedback they are receiving from their peers:

What this means: you can trust the feedback coming from your peers about whether or not your drafts contain all the specified features. Use these as you begin drafting to turn your attention to those things that were not present or not as detailed as they could have been.

Next, I’ll try to interpret a bit and even pull out some good examples that they identified during their reviews (and which I think everyone can learn from):

Trait Matching – Summarizing Patterns, Including Detail, and Analyzing

I’m happy to say that on the whole, folks did a good job summarizing their own data. Almost everyone (88%) included a summary of media use patterns and (85%) supported these with detailed evidence. Of the few who were rated by peers as deficient in this area, they often merely listed statistics and did not frame these in terms of a pattern. The following example is modified, but shows what I mean:

List rather than summarize “I sent 27 text messages on Wednesday and 41 on Thursday. I received 18 texts on Wednesday and 51 on Thursday.”

Summarize, rather than list:

“My weekday texting activity seemed to depend on how much time I spent at work on a given day. On my day off, Wednesday, I sent just a little under twice the number of texts than I did on Tuesday, a day when I worked. I also received more texts on my off day, likely because I was engaged in longer conversations than I would be if I were at work.”

See how example one is just the facts, while example two identifies a use pattern that the facts support? That’s a key difference.

But by far, the biggest shift most of you will make as you draft your essays is from summarizing to analyzing. This makes sense, but will be a challenge as you also need to incorporate secondary source data. Note that only 68% of you “Described the relationship between two or more patterns” and just “65% provided evidence to explain the relationship between two or more patterns.” As I read the drafts, I’d put those numbers just a little bit lower – you were generous with one another in your reviews this time! 🙂

Of course, these are just my comments to the whole group. For individual students, I can drill down further and say something like this:

Having this evidence makes all the difference when it comes to getting students to see a writing assignment as a way to identify what kinds of writing moves they need to improve (vs. those that they are doing well) and to practice those things in a deliberate way.

References

Kellogg, R. T., & Whiteford, A. P. (2009). Training advanced writing skills: The case for deliberate practice. Educational Psychologies, 44(4), 250–266.